Building a School-Wide Culture of Thinking: Leadership Strategies for Lasting Change

FEBRUARY 19, 2025

Walk into a truly great school, and you’ll feel it right away—a sense of curiosity, inquiry, and deep engagement. Students don’t just memorize facts; they make connections, ask questions, and think critically about what they’re learning. Teachers aren’t just delivering lessons; they’re guiding students through a process of discovery. This doesn’t happen by accident. It happens because school leaders make a conscious effort to build a culture of thinking.

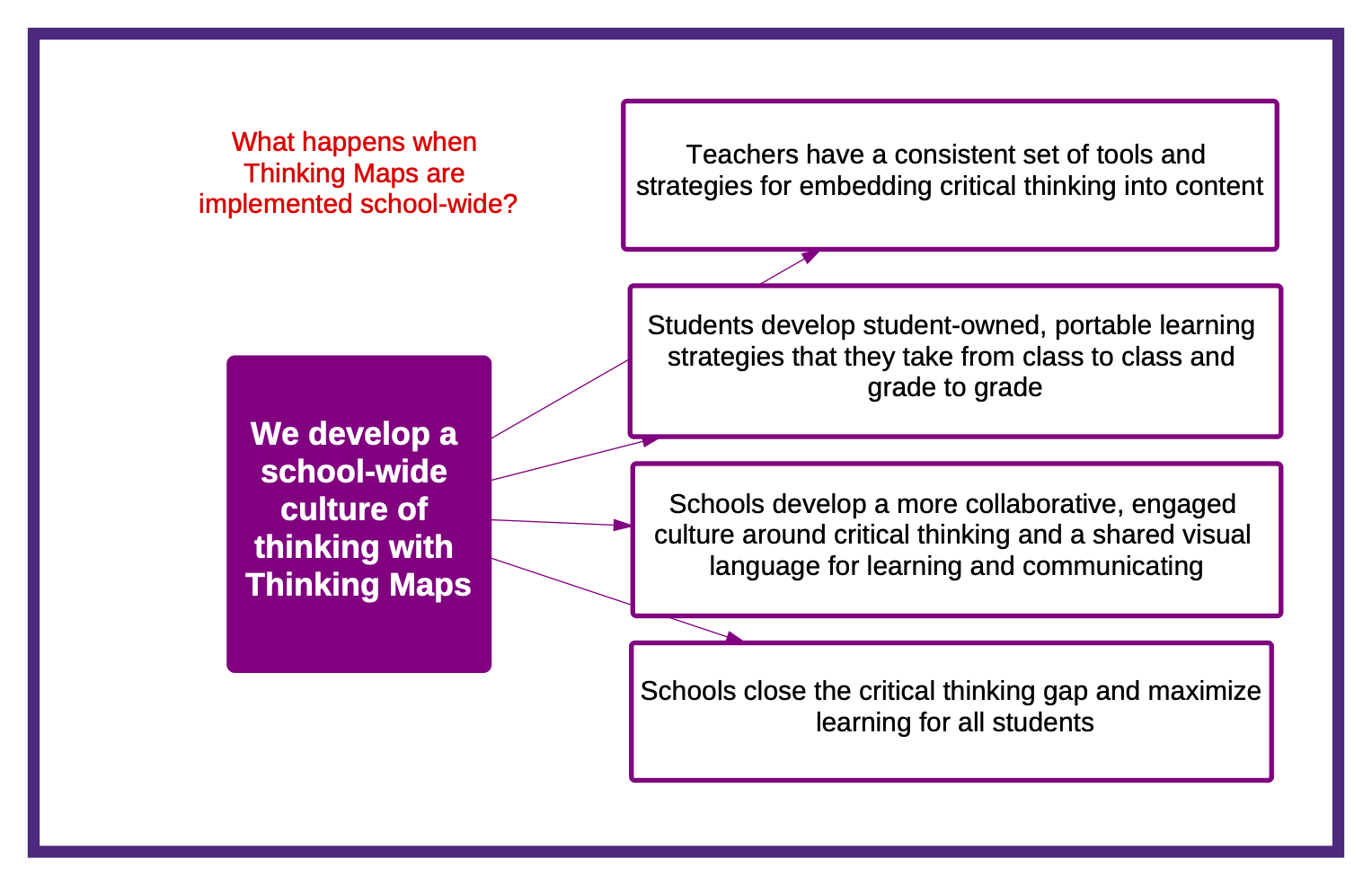

In a Thinking Maps school or district, critical thinking extends beyond the classroom walls. Students develop ownership in portable learning strategies that they carry with them from class to class and grade to grade. Teachers elevate planning and collaboration using a shared vision and strategies. School and district leaders are key elements of successful, lasting whole-school change built around critical thinking.

What Is a School-Wide Culture of Thinking?

Thinking Maps is intended to be implemented across a whole school—or, ideally, a whole district. Why does that matter? A school-wide culture of thinking means that critical thinking isn’t just an occasional classroom activity. It’s a consistent, intentional practice embedded into every lesson, across every grade level and subject. It means that students, teachers, and administrators speak the same language of thinking, using a shared set of tools to organize ideas, analyze information, and communicate more effectively. In a Thinking Maps school, that shared language for thinking consists of a set of consistent visual patterns that represent core thinking processes.

A whole-school approach helps to close the critical thinking gap and empower students with the skills they need to succeed in school, college and career. Schools using Thinking Maps school-wide are more than 2x as likely to surpass average district growth rates in both reading and math.

The Role of Critical Thinking in Student Success

Critical thinking is the cornerstone of learning—not just in the classroom, but in all facets of life. To truly understand and retain what we are taught, we must actively engage with content and ideas. Critical thinking fosters this engagement by encouraging students to question, analyze, and connect concepts, laying the groundwork for meaningful and lasting learning.

One key aspect of this process is schema building—the creation and refinement of mental frameworks that organize and store knowledge. As students engage in critical thinking, they integrate new information into their existing schemas, deepening their understanding and making it easier to recall and apply knowledge in new contexts. For example, when learning about ecosystems, a student might link this new information to prior knowledge about food chains, environmental conservation, or personal experiences with nature. These connections not only enhance comprehension but also enable students to think more flexibly and solve problems more effectively.

In the classroom, critical thinking and schema building empower students to move beyond surface-level memorization to develop a deeper understanding of complex concepts. They learn to identify patterns, evaluate evidence, and construct logical arguments. These skills are equally vital as students move through postsecondary education and into the workforce.

When Thinking Maps are used school- or district-wide, students don’t have to “relearn” new strategies every year. Instead, they build on their skills from elementary through high school, refining their ability to think critically, solve problems, and articulate their understanding. Unlike the hundreds of disparate graphic organizers, which are not grounded in cognitive science and may only be used for individual assignments, Thinking Maps uses eight consistent visual patterns tied to eight core cognitive processes. By using these patterns and their associated academic vocabulary consistently across classes and grade levels, students develop automaticity with critical thinking skills. Building portable, student-owned learning strategies is a powerful agent for whole-school change. That means they can spend more time focusing on content, leading to higher learning gains.

For teachers, a school-wide culture of thinking means they are no longer working in isolation—it creates a collaborative, structured approach to planning and instruction. With Thinking Maps as a shared tool, teachers across grade levels and content areas have a common framework for lesson design, student support, and professional dialogue. Collaboration becomes more purposeful as teachers align instruction, analyze student work using the same cognitive processes, and build on the thinking skills developed in previous grades. Instead of reinventing strategies each year, teachers can focus on deepening content knowledge and addressing standards.

The Difference a Leader Makes

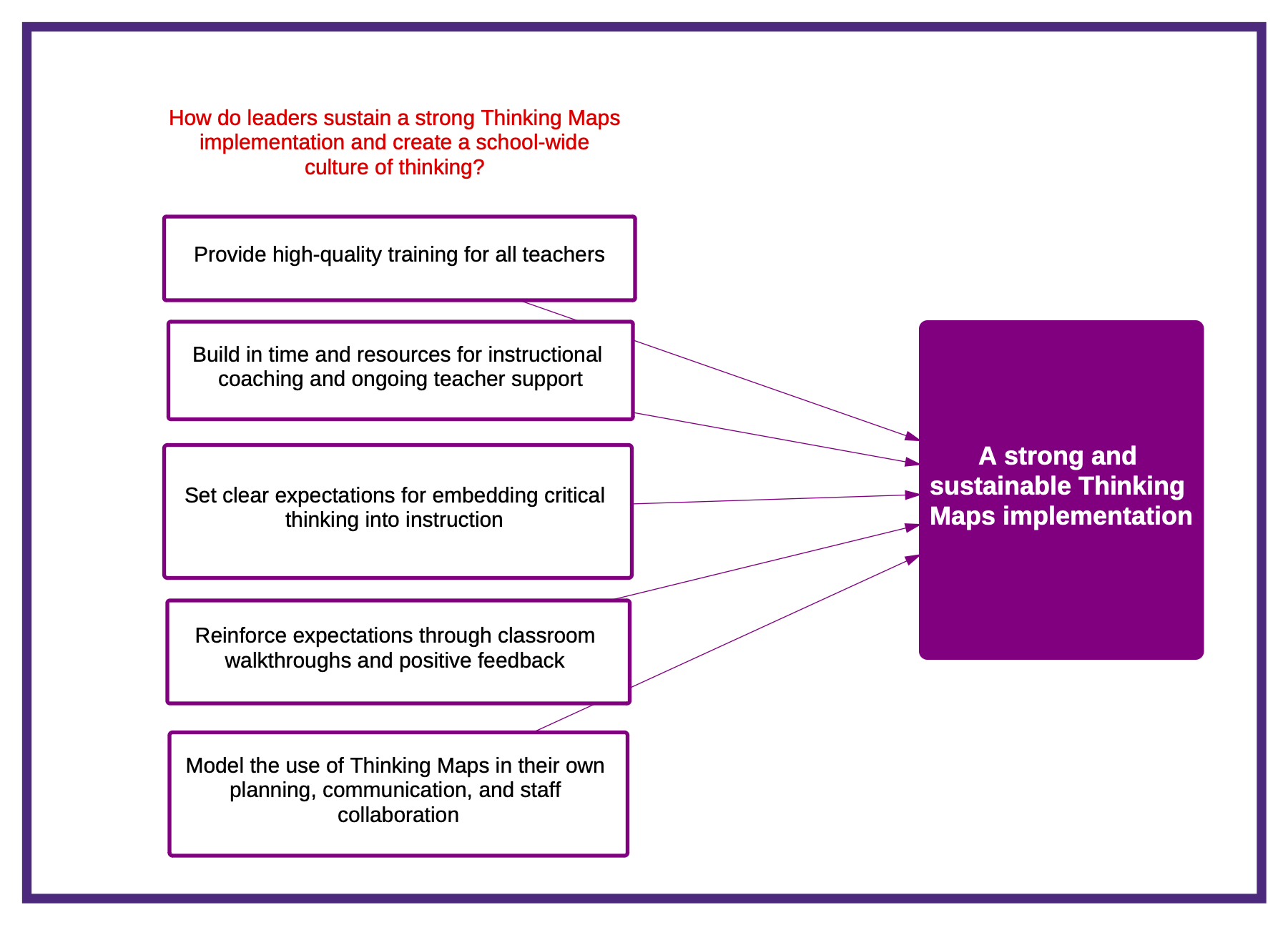

What is the key element in every stand-out Thinking Maps implementation? A great leader. Leadership makes the difference between a school where Thinking Maps is just another strategy and one where it transforms the way students and teachers engage with learning.

A strong leader sets the vision for a school-wide culture of thinking, ensuring that critical thinking isn’t just encouraged but is deeply embedded in everyday learning. They don’t just tell teachers to use Thinking Maps—they model their use in professional learning, decision-making, and communication. They provide teachers with ongoing support, training, and opportunities to collaborate, ensuring that Thinking Maps becomes an integral part of the school’s instructional framework rather than an isolated tool.

- Victor Elementary School District (CA) made Thinking Maps and Write from the Beginning…and Beyond a core component of their reading certification program, which all of their teachers complete. Thinking Maps are now infused at every level of the district, from the classroom to the boardroom and across every grade from TK–6. This strong commitment by school and district leaders earned the district a California Pivotal Practice Award.

- In Maricopa Unified School District (AZ), district leaders, including Assistant Superintendent Sheryl Redner and Director of Curriculum and Instruction Wade Watson, implemented a district-wide Thinking Maps initiative. It started with a commitment to consistent, high-quality training for all teachers across the district, followed up by ongoing coaching support. At the school level, instructional rounds and frequent staff discussions help to sustain the change.

- At Concourse Village Elementary School (NY), Principal Alexa Sorden made Thinking Maps a foundational tool from the school’s inception, ensuring every teacher was trained and using Thinking Maps consistently. She fostered a unified instructional approach aligned with Common Core standards, leading to transformative gains in student achievement.

- At Desert Rose Elementary School (CA), Principal Melanie Pagliaro led a school-wide Thinking Maps implementation to support diverse learners, particularly English Learners. She ensured consistent use across all grade levels and introduced the Path to Proficiency program to accelerate language acquisition. This structured approach led to significant academic gains, embedding Thinking Maps into the school’s learning culture.

- At Kenilworth Elementary School (AZ), Thinking Maps are highly visible throughout the school, from classrooms and hallways to leadership meetings. Principal Anthony Pietrangeli ensured sustainability by becoming a Thinking Maps trainer alongside 15 teachers, embedding the tools into daily instruction and professional learning. His lead-by-example approach helped establish Thinking Maps as a school-wide habit, with students using them independently to structure their thinking.

- At Shumway Leadership Academy (AZ), Thinking Maps are infused across all content areas as well as into teacher collaboration and planning. Principal Dr. Korry Brenner says a whole-school approach has not only driven gains for students, including English Learners, but has also transformed the school culture. “It’s no longer about what “I” do but about what WE do together,” she says.

Here’s how school and district leaders make Thinking Maps a long-term success:

- They set the vision. A school-wide culture of thinking starts with leadership articulating why critical thinking matters and how Thinking Maps will be used to achieve that goal.

- They invest in training. A one-time workshop isn’t enough. Strong leaders ensure that teachers receive ongoing professional development, coaching, and support so they feel confident and skilled in using Thinking Maps.

- They model Thinking Maps in their own work. When principals and district leaders use Thinking Maps in meetings, planning, and communication, it reinforces their value and importance.

- They make Thinking Maps a shared, school-wide practice. Thinking Maps are most effective when used consistently across grade levels and subjects. Leaders help teachers collaborate and align their instruction so that students experience a seamless approach to thinking.

They sustain momentum. Transforming a school culture doesn’t happen overnight. Strong leaders continuously assess progress, provide feedback, and celebrate successes, ensuring that Thinking Maps remains a long-term instructional priority.

A school-wide culture of thinking doesn’t happen by chance—it happens because leaders make it a priority. When principals and district leaders champion Thinking Maps, they create a shared language for learning that empowers students, strengthens instruction, and transforms school culture. With a consistent, research-backed framework for critical thinking, students don’t just complete assignments; they develop skills that will serve them for life.

More on Thinking Maps and Leadership:

- How to Close the Critical Thinking Gap

- Building a Culture of Continuous Learning for Teachers

- Building Strong Professional Learning Communities

- Building Great Teacher Leaders

More on Navigator

(For Thinking Maps Learning Community subscribers only. Not a subscriber? Contact your rep to get started!)

Continue Reading

July 2, 2025

A Meta-Analysis of studies showed that coaching, along with group training, curricular and instructional resources made a larger impact on the effects of teaching and student achievement.

October 10, 2022

To celebrate National Principals Month, enjoy these pieces on equity, SEL, PLCs, and building whole-school cultures for continual learning.

September 13, 2021

During the Assess phase of the Professional Development cycle, teachers look at the outcomes that they have achieved and determine whether or not the application was effective.

August 9, 2021

Application is a critical step in the Professional Development cycle. To facilitate lasting change in the classroom, teachers must be able to apply what they have learned.