How to Close the Critical Thinking Gap

FEBRUARY 15, 2024

A majority of teachers believe that students are finally catching up from pandemic learning losses. But those gains are far from evenly distributed—and too many students were already behind before the pandemic. To close these achievement gaps, schools and districts need to focus on the underlying issue: the critical thinking gap. By integrating critical thinking with content-area instruction, we can help students accelerate academic gains and develop the cognitive skills they need for college and career success.

Critical Thinking and Academic Equity

When we talk about achievement gaps in K-12 education, we’re often talking about performance gaps on standardized tests, either state assessments or the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), often known as “The Nation’s Report Card.” These tests are designed to measure students’ knowledge and skills in relation to state-defined academic standards. To perform well, students need both content knowledge (including specific facts, concepts, and information taught within subject area classes) and critical thinking skills. Most modern standardized tests require students to go beyond basic recall to:

- apply knowledge and skills in new contexts;

- analyze, evaluate and develop arguments;

- draw conclusions or inferences from text or data;

- synthesize information from multiple sources; and

- apply higher-order thinking and reading comprehension skills to complete response-to-text activities.

The achievement gap on K-12 standardized tests reflects disparities in both content knowledge and critical thinking skills. In fact, these two elements are highly interrelated; mastery of content knowledge provides the foundation upon which critical thinking skills can be developed and applied, while critical thinking skills are essential for comprehension, retention, and application of grade-level content.

That’s why some experts believe the achievement gap is largely a critical thinking gap. Colin Seale, an education activist and the author of Thinking Like a Lawyer: A Framework for Teaching Critical Thinking to All Students (Prufrock Press, 2020) and Tangible Equity: A Guide for Leveraging Student Identity, Culture, and Power to Unlock Excellence In and Beyond the Classroom (Routledge, 2022), sees critical thinking as an equity issue. In an interview with ASCD, he says:

When you start to look at how critical thinking looks in practice in K–12 classrooms, it’s often being treated as a luxury good. You’ll see critical thinking in an after-school mock trial program, or for an honors program that serves 8 percent of the school population, or for the special debate team or the selective entry school.

To close the achievement gap, we need to also (or first) close the critical thinking gap. Critical thinking skills are an important component of college and career readiness and provide an essential foundation for success in life. When they are taught in isolation or only to certain students, we are guaranteeing that many students will continue to fall further and further behind their peers on academic attainment and career opportunities.

And we know exactly which students these are: Students in schools serving high-poverty or high-minority populations are less likely to receive specific instruction in critical thinking skills. Students in special education (SPED), English Learners (ELs), and students receiving other forms of intervention are also less likely to be part of higher-level classes or extracurricular opportunities (such as debate teams) where critical thinking skills are taught and emphasized.

And yet, we know that all students benefit from direct, explicit instruction in critical thinking. Closing the critical thinking gap for underserved and underperforming students will not only increase their odds of success with grade-level content and standardized tests but will also set them up for higher levels of achievement throughout their lives.

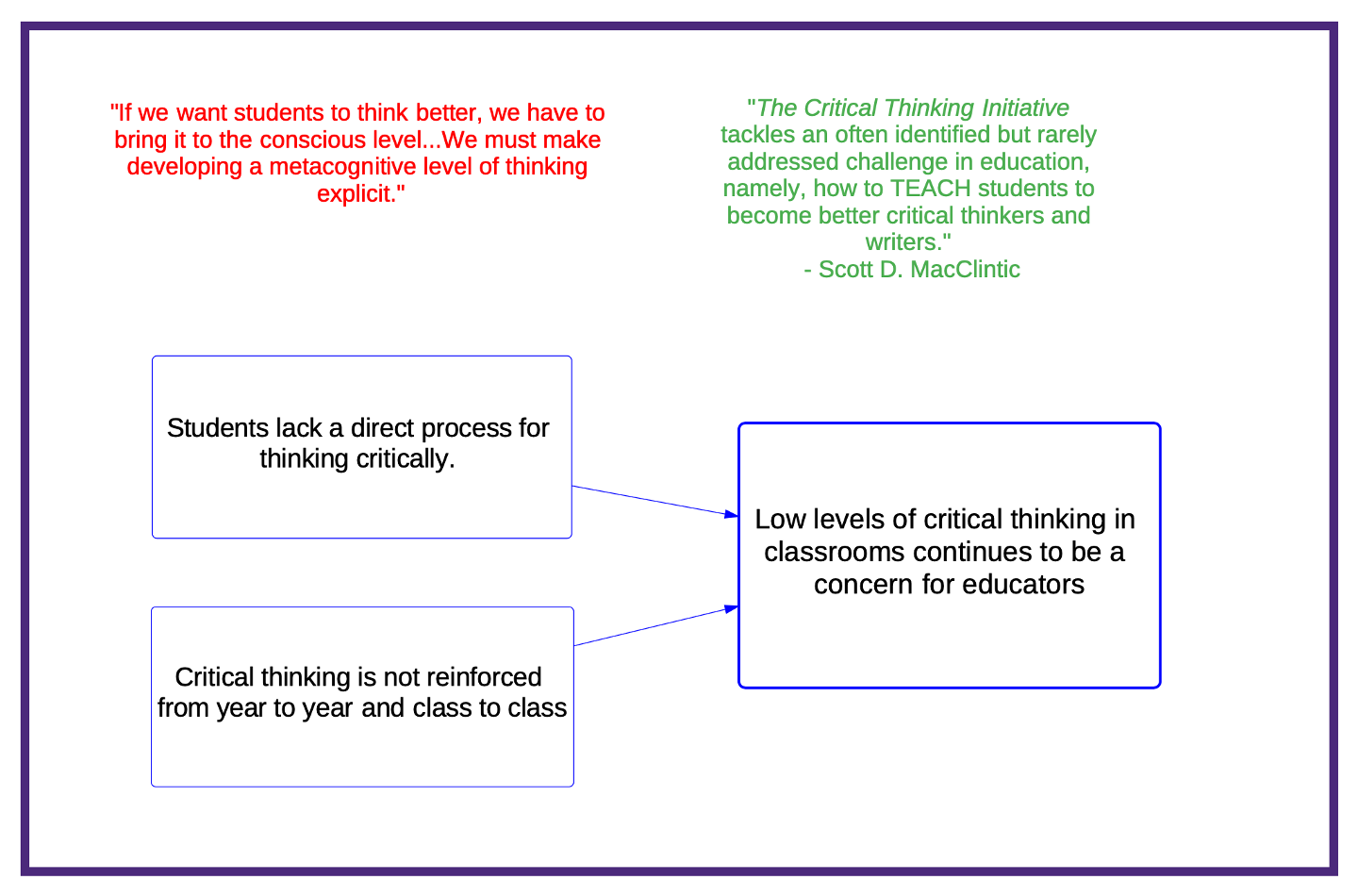

Why Don’t Schools Teach Critical Thinking?

If critical thinking is so—well, critical—why aren’t more schools stressing critical thinking instruction? Surveys show that critical thinking is sadly under-emphasized in our schools, especially in the middle grades when students are at an ideal cognitive stage to develop many of these skills. There are several reasons that teachers cite for not teaching critical thinking skills.

- They don’t have time for something “extra” in the school day. When critical thinking is taught as an extra unit or an additional set of activities outside of the core curriculum, it becomes a burden for both teachers and students. Teachers are already under pressure to cover a wide range of state standards while also differentiating instruction for students who need extra help or extra challenge. It’s no wonder they don’t feel like they have room for one more thing in the curriculum.

- They lack the necessary training and expertise. Most content-area teachers were not explicitly taught how to teach critical thinking in their teacher training programs. And most school districts do not set aside curricular budgets or professional development time for critical thinking programs. As a result, a majority of teachers feel like they don’t have enough expertise to tackle critical thinking in the classroom. In a report from the Reboot Foundation, surveyed teachers consistently mentioned a need for more resources and updated professional development in critical thinking.

- They don’t believe it is a priority. While state standards and state assessments have put more emphasis on critical thinking skills in recent years, teachers may not recognize the need to explicitly and systematically teach critical thinking along with content knowledge. Teaching and assessing knowledge of concrete facts is much easier than engaging students with high-level discourse around academic content. Especially at the secondary level and beyond, some teachers believe that their job is to focus solely on their content area. Other teachers may believe that thinking skills develop naturally in students and do not require explicit instruction.

To Close the Achievement Gap, Close the Critical Thinking Gap

When students are falling behind grade level standards, the first response is often to double down on very basic skills or focus on closing content gaps. But what most students need is not more repetition of basic facts, but better cognitive skills. When we focus on thinking first, students catch up faster, because they know how to learn.

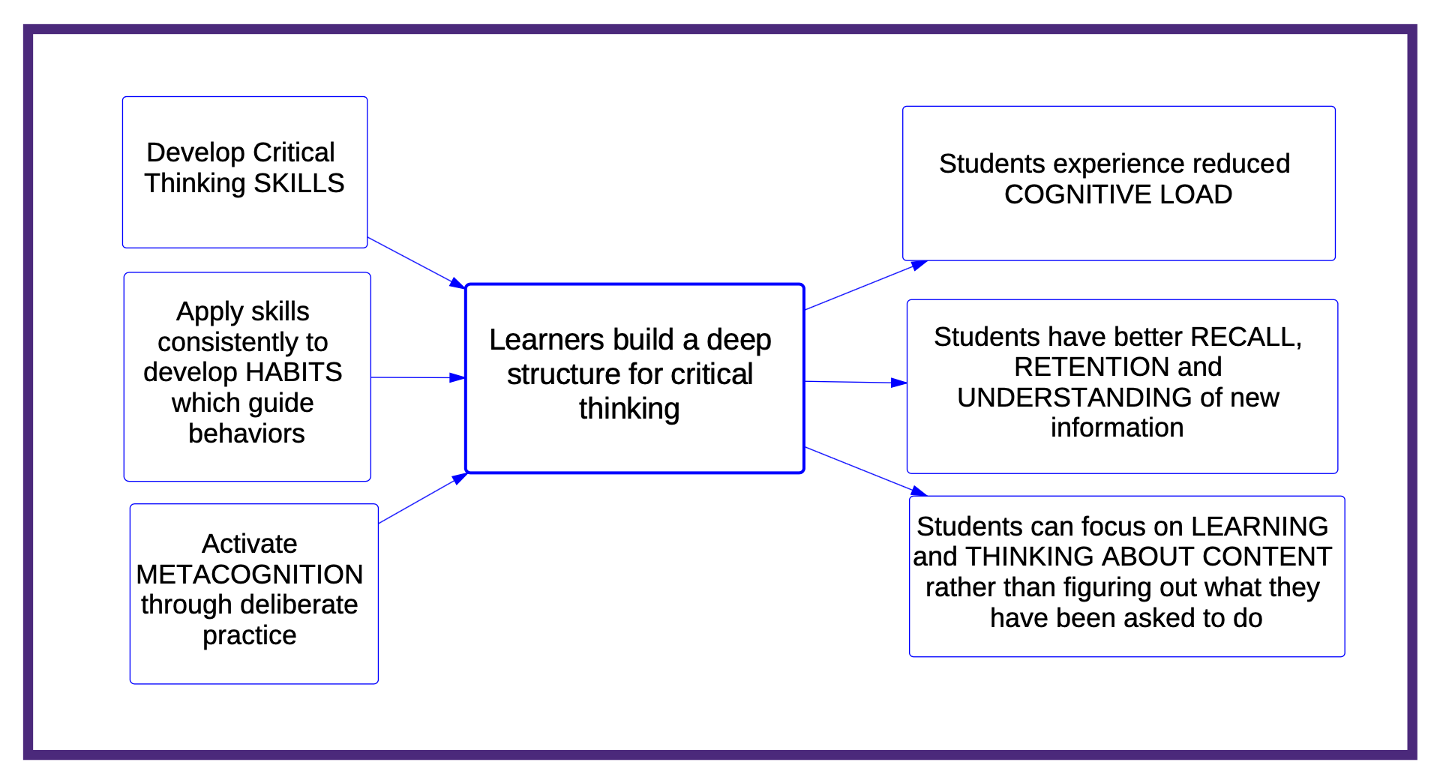

Closing the critical thinking gap requires more than a six-week critical thinking unit or a set of supplemental activities. For best results, critical thinking must be taught and developed in tandem with content knowledge. Critical thinking is not something “extra” for teachers to do, but rather a core element of the curriculum.

Thinking Maps give teachers a practical set of tools and strategies to incorporate critical thinking into the curriculum. With Thinking Maps, teachers can address both halves of a learning standard simultaneously: the content students are meant to learn and the type of thinking the learning task requires. When we approach critical thinking this way, it actually saves time for teachers and students in the long run by making learning more efficient. Integrating critical thinking with content improves understanding and recall of content knowledge and reduces the cognitive load of learning while developing the cognitive skills students need to think flexibly and deeply about any subject.

When Thinking Maps are used across all grade levels and subject areas, they become portable learning strategies that students learn to apply independently to any type of content, task or problem. As students develop these critical thinking skills, they become more efficient learners and are better prepared for life after high school. Teachers, in turn, have more time to delve deeply into subject-area content and engage students with higher-order tasks and projects. By closing the critical thinking gap, we can help all students accelerate learning.

Want to learn more about Thinking Maps and critical thinking? Join our upcoming webinar on February 21: Building a Deep Structure for Critical Thinking.

Continue Reading

November 24, 2025

Critical thinking is having a moment in education, but in many classrooms, it is still more slogan than reality. Drawing on their district- and classroom-level work with Thinking Maps, we were joined by four practitioners who shared what it really looks like to build a culture where students—not teachers—do the heavy cognitive lifting. Here are their 5 key takeaways.

October 16, 2025

Across classrooms today, artificial intelligence is reshaping how students access and produce information. While AI can generate answers instantly, it often interrupts the deeper process of thinking and reflection that makes learning meaningful. The challenge for educators is not whether to use AI, but how to ensure students continue to engage in authentic, critical thought when it is present.

May 1, 2025

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is transforming education, from custom content in a minute to personalized learning. But with this surge in AI adoption comes a critical challenge for educators and students alike—the need to strengthen critical thinking skills. While AI offers immense potential, it cannot replace the human ability to think analytically, question assumptions, and make independent judgments.

January 15, 2025

Rather than simply memorizing facts, students with strong critical thinking skills learn how to connect ideas, identify patterns, and make informed decisions—key abilities in a rapidly changing world. These higher-order thinking skills at the core of critical thinking push students beyond rote learning to actively engage with content. In fact, closing the critical thinking gap is one of the most effective ways to accelerate learning for students who are struggling to learn grade-level content.